What did the Confederates believe? Could you explain their ideology? As I mentioned in starting this project, I didn’t have much idea myself, but what I did know made me think that nothing resembled today’s Trumpism so much as Confederate politics. Now that I’ve done a bit of reading, I remain convinced.

Let’s start with the basics. Most Americans are aware of the Civil War, and most would say that it had something to do with state rights and/or slavery. In fact, much of the modern debate around the Confederacy, monuments to it, and white supremacy seem to hinge on which of these concepts came first in importance. Did we fight the Civil War to end the slavery of African Americans in the South, or did we fight it to settle once and for all whether states must bend to the will of the federal government?

Surveys say many Americans lean toward the state’s rights angle, say 41 percent. When they seceded, the Southern States said it was about slavery, as Ta-Nehisi Coates hammered home in this 2015 story in the Atlantic (written in the wake of South Carolina removing the Confederate Battle Flag from its capital grounds).

An ideology can be more complex than a single cause, and certainly Confederate thought was a contradictory blend of conservative politics and racial republicanism. If we want to understand what is happening in our country right now, we should look to how these and other ideas formed an ideology that remains a force in the United States.

We can start with just those two most famous Civil War concepts: states’ rights and slavery. And we can be clear: slavery was the biggest issue on southern minds when they stopped being Americans and became Confederates. Courtesy of Coates, here’s Alabama’s stated reasons for secession:

“Hence it is, that in high places, among the Republican party, the election of Mr. Lincoln is hailed, not simply as it change of Administration, but as the inauguration of new principles, and a new theory of Government, and even as the downfall of slavery. Therefore it is that the election of Mr. Lincoln cannot be regarded otherwise than a solemn declaration, on the part of a great majority of the Northern people, of hostility to the South, her property and her institutions—nothing less than an open declaration of war—for the triumph of this new theory of Government destroys the property of the South, lays waste her fields, and inaugurates all the horrors of a San Domingo servile insurrection, consigning her citizens to assassinations, and. her wives and daughters to pollution and violation, to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans.”

In diving into Civil War history, I was struck by how quickly war followed the election of President Abraham Lincoln in 1860. In an echo of today, many Americans refused to accept the legitimacy of the elected president, and also acted with repulsion at the choice of the majority of their fellow citizens. Before Lincoln could even make it to Washington D.C. to be inaugurated, Southern states, led by South Carolina, began leaving the union. If California felt as strongly now as South Carolina felt then, it would have left the union before President Donald Trump had a chance to dispute the crowd size at his own inauguration.

Look at that Alabaman line again about “the inauguration of new principles, and a new theory of Government.” That’s the states’ rights piece, but not the way we think of it now. Turns out the concept that the Northern states, by virtue of being a majority of the population, could leverage the federal government to end the economic engine of slavery was mind-boggling and outrageous to southern politicians.

They had reason to be boggled, at least on paper. The Constitution explicitly allowed for slavery and the federal government had never been so powerful before.

“Secessionists, in their view of themselves, were attempting to restore the Constitution, protecting state sovereignty from northern aggression,” wrote Zachary S. Brown of Stanford University. While people on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line saw the times as revolutionary, he wrote “the South saw this revolutionary world as a threat, designing the rhetoric of secession such that it ‘fit the model of pre-emptive counterrevolution.’”

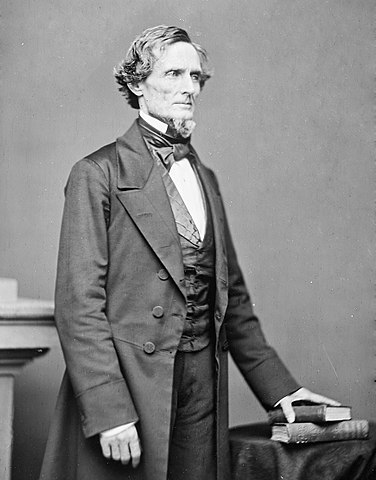

Catch that? The Confederates thought that the Northern concept of government – the government that every American generation has inherited since – was a betrayal of American ideals. The Southern states left the union, and fired the first shot. But they saw the North as the revolutionary, not themselves. No one hammered on this idea more than Jefferson Davis, the first and last president of the Confederate States of America. He presented the Confederacy to both the north and to potential European allies as principled conservatism, a group of states that refused to go along with the radical federal notions of the Republican Party.

“The principles of the Constitution have been corrupted,” Davis told the Confederate Congress in 1861. He said Lincoln wrongly thought “that in all cases the majority should govern.”

The problem, of course, was that the Confederacy quickly found itself fighting for its survival against a foe with more money, people and supplies. It lacked cohesiveness, political parties and competitive elections, but it needed more of everything a federal government could provide. Although the war was prompted by the threat to end slavery, “states’ rights” was more than a slogan in the South, wrote another history professor, Michael Todd Landis. It was so dearly held as an ideal, it hampered the Confederacy’s efforts to survive:

“Much of the trouble was due to rebel devotion to states’ rights ideology. The weak Confederate government was unable to manage the powerful, fiercely independent states it supposedly led. Congressional legislation was frequently stalled by fights over how and where money should be spent, Davis’s leadership was constantly undermined by honor-minded generals vying for command, and military campaigns were often hindered by states refusing to send troops and supplies.”

In facing down annihilation, the Confederates had to choose between being independent states and a single nation.

And here’s the important thing: They chose to be a nation. A white nation.

The demands of the war effort required a sense of nationalism, argues Brown. Principles of constitutional government would not do, not when those principles apparently allowed each state to do as it wished in the middle of a war. What arose was the triumph of the slavery side of the coin: one Southern nation, yes, but one founded on white supremacy.

“What made this white republican ideology so different from the rhetoric of constitutional integrity and state sovereignty, which was central to the conservative counter-revolution, was that it was … explicitly racial,” Brown noted.

How explicit? The Confederates began working on new school books that would not only cover the history of the Roman Empire, but call out its use of slaves for approval.

Let’s acknowledge that the Northern states, by now the “Union” side of the war, were not free of racist thought. The Democratic Party was a minority in Congress, especially after the secession of the southern states. But amid the bloodshed of war and the growing Republican appetite for the end of slavery, the Democrats campaigned on white fears in the 1862 elections. Landis writes:

“They made emancipation the central issue of the campaign and employed fear tactics to exploit Northern racism. They claimed ‘Black Republican’ leaders were part negro, warned of an impending race war between blood-thirsty former slaves and innocent whites, and asserted that freed blacks would steal white jobs. Anti-black poems, songs, posters, newspaper cartoons, and pamphlets were widely distributed, leading to anti-black riots throughout the North.”

It takes less people to riot than to win elections, though. The most important thing about these Northern racial appeals is that they didn’t work. They won a few elections for the Democrats, but they didn’t turn the political tide. The Republican Party, campaigning on winning the war (peace through victory) and the emaciation of slaves (not racial equality), would strengthen its standing in Congress in 1862, and re-elect Lincoln in 1864. They amended the Constitution to forbid slavery.

In the end, the Confederates lost the war and so did the Democrats. The Republican Party would dominate politics for a generation. The “Lost Cause” mythology would come to smooth over explicit support for slavery, in favor of the states’ rights argument of Jefferson Davis.

Thus, Southerners before and after the war would defend themselves against the Northern majority with Constitutional arguments. Even among themselves, the cause of slavery was gone.

Nonetheless, in war the soft metal of Confederate thought had been tempered into something more dangerous. No longer a contradictory mix of diffuse government power and slave-owning economics, the core of Confederate ideology had solidified around a concept we all recognize today: desire for a white American republic.

How that vision has lasted for 150 years, and how widely it is shared today is quite the question.